About Us

Who We Are

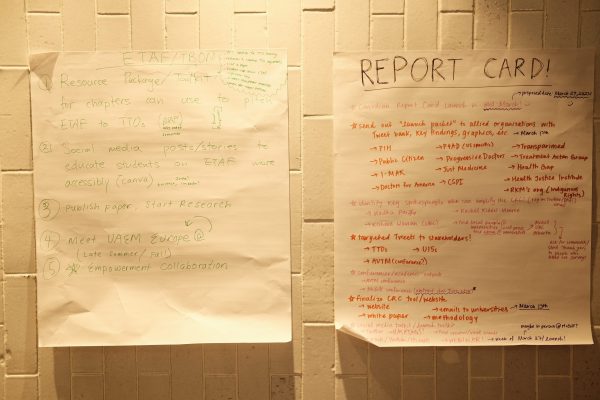

UAEM’s Canadian Report Card project evaluates 15 of Canada’s research-intensive universities on their contributions to biomedical research on neglected health needs, access to medicines, and education concerning access and innovation issues. By collecting data from the universities regarding their innovation, accessibility, empowerment and transparency on their biomedical R&D practices, we aim to critically and accurately depict Canadian research practices as well as point out specific areas of improvement to serve as a base for student advocacy within the individual universities.

Project Summary

UAEM’s Canadian Report Card project evaluates 15 of Canada’s research-intensive universities on their contributions to biomedical research on neglected health needs, access to medicines, and education concerning access and innovation issues. The Report Card uses both publicly available and self-reported information to evaluate academic institutions on three key questions:

- To what extent are universities investing in innovative biomedical research that addresses the neglected health needs of resource-limited populations?

- When universities license their medical breakthroughs for commercial development, are they doing so in ways that ensures equitable access for all marginalized and vulnerable populations in high, middle and low-income countries? What steps are they taking to ensure innovative treatments are made available at affordable prices?

- What efforts are universities making to educate the next generation of global health leaders about the crucial impact that academic institutions can have on global health through their biomedical research and licensing activities?

Why is this needed?

Universities are major drivers of medical innovation. Between 1/4 and 1/3 of new medicines originate in academic labs, and universities have contributed to the development of one out of every four HIV/AIDS treatments (1). There is enormous potential for universities to leverage their investment in biomedical research to advance global health. However, the size and scope of this impact depend on decisions about where to focus research, how to share new discoveries, and what to teach a rising generation of young global health leaders.

More than 1.7 billion people worldwide suffer from ‘neglected diseases’ – illnesses rarely researched by the private sector because most of those affected are too poor to provide a market for new drugs, and over 1 billion of them are children (2,3). Furthermore, 10 million people die each year simply because they can’t access existing lifesaving medicines – often because those treatments are simply too expensive (4). With new global health challenges such as COVID-19, HIV/AIDS, antimicrobial resistance, the lack of transparency in research, including for clinical trials, and the lack of alternative models for efficient and sustainable innovation, the gap between vulnerable populations and affordable treatment threatens to widen even further. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic largely showed the immense gaps between low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and high-income countries (HICs) when it comes to sustaining a functioning healthcare system as well as massively vaccinating their population.

Universities can use their unique positions as public interest, largely publicly funded research institutions to address both of these challenges. By prioritizing research on global diseases neglected by for-profit research and development (R&D), they can pioneer new treatments that will benefit millions in LMICs. And by sharing their medical breakthroughs under open, non-exclusive licenses or licenses that promote lower prices for LMICs and for underserved populations in HICs, universities can help poor patients worldwide access new, lifesaving treatments. Universities can also play a critical role in educating their students and raising awareness within and outside of their campus about these issues in order to empower them to take on these global health challenges in their own work.

Some universities are already taking these steps – along with teaching students about the challenges of neglected disease innovation and treatment access. However, few have systematically tried to measure universities’ contributions in these vital areas. UAEM’s University Report Card fills that gap. The first iteration of the Report Card, released in 2013, evaluated both American and Canadian institutions together. However, major Canadian universities differ in key respects to their American counterparts in regard to biomedical research funding, which is why the 2017 iteration of the Report Card evaluated the Canadian and American universities separately.

Compared to 2017, most universities have regressed in all sections, with access and empowerment receding the most. This indicates that universities invest fewer resources into offering global health-related courses and/or programs for students at all levels, disregarding the need to educate and raise awareness among our future leaders. This is accompanied by an overall decrease in access, with a reduction of universities signing non-exclusive licensing agreements, less trial data made public than ever before, and fewer publications in open-access format. The COVID-19 pandemic proved that publishing in open-access journals and sharing data and knowledge is more than possible and was highly incited, showing that universities make conscious choices to avoid doing so.

- (1) Kneller, Robert The importance of new companies for drug discovery: origins of a decade of new drug, Nature Review Drug Discovery, 2010

- (2) Sampat, Bhaven Academic Patents & Access to Medicines in Lower- and Middle-Income Countries, American Journal of Public Health, 2009

- (3) Hotez PJ, Molyneux DH, Fenwick A, Kumaresan J, Sachs SE, Sachs JD, et al. Control of neglected tropical diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357(10): 1018-27.

- (4) World Health Organization. Equitable access to medicines: a framework for collective action. Policy Perspectives on Medicines, 8: 1-6. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

This will be the second entirely Canadian iteration of the University Report Card. This report follows the release of the 2017 Canadian University Report Card as well as the 2020 US University Report Card. The new methodology for the 2023 Canadian Report Card is provided below.

Support for the Report Card:

“Canadian universities play a critical role in addressing global challenges such as HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and other neglected diseases. It is imperative that we continue to give priority to the lives of millions through licensing practices that allow our world-class research to reach those that need it most. This Report Card helps us measure the impact our universities have on global health. It clearly shows Canadian Universities are falling short: students, faculty and related communities must jolt the universities into sanity.”

–Stephen Lewis,Co-Director of AIDS-Free World, Canada’s Former Ambassador to the United Nations

“The UAEM Canadian Global Equity in Biomedical Research Report highlights a worrying lack of transparency on publicly funded biomedical research carried out by Canadian universities. With only a third of clinical trials data disclosed and only one university adopting global access licensing, this Report Card proves once again that universities have a long way to go. It is time for universities to fulfill their responsibility to ensure that publicly funded biomedical research is available for the public good.”

–Rachel Kiddell-Monroe, ISID Professor of Practice McGill University

Previous

Next